“What is love?

Oh, baby, don't hurt me

Don't hurt me no more”

~ Haddaway

I was seven years old when my family and I emigrated from Kurdistan, settling in our new homeland of Canada, a country known for its exceptionally large landmass, beautiful vistas, and unforgiving winters. As a highlander hailing from the Zagros mountains, I was not exactly a stranger to cold and snowy climates, so it was not the weather of my new home so much as her culture that astonished me the most as a child. About a year into our transition to Canada, a musical craze swept over North America—a Eurodance music video to be more specific, released in 1993, with a catchy, upbeat tune that has garnered close to 400 million views on YouTube so far. The title of the song is “What is Love,” the very question I will attempt to answer from the perspective of neuroscience in this issue of ZAGROSCIENCE.

Love can mean many things to many people: it is the perennial theme of poetic and narrative discourse, the spark that romantically binds two souls together, the reason parents would die to protect their children, the impetus that rallies people behind a unifying cause, but also the fuel that drives some into madness, chaos, and war. It is, in a very real sense, one of the most powerful forces of nature—human nature that is, which is to say, the product of the human brain. So how, then, does the cortex instantiate love?

A leading conceptual framework known as the Neurobiology of Human Attachments Model maintains that mammalian bonding recruits a neurocircuitry that is shaped by the relationship between mother and offspring in the early stages of life. Proposed by Feldman (2017), it posits that the neural machinery that originally subserves mother-child affection is at the core of other types of interpersonal attachment that may develop later in life, such as romance or friendship. This model also recognizes the importance of the dopamine and oxytocin signalling pathways in sustaining bonding behaviours. One of the primary functions of the dopamine system is the regulation of reward and pleasure, a topic I have already covered in great depth in the context of addiction:

Oxytocin, on the other hand, sometimes referred to as the “love hormone,” plays a crucial role during childbirth, breastfeeding, mother-child bonding, and other forms of interpersonal dynamics. Secreted by the hypothalamus and released via the posterior pituitary gland into the bloodstream, it is known to induce uterine contractions, facilitating the birthing process. Inside the mammary glands, its action allows for milk to be let down into the lactiferous ducts, whereupon it is ejected into the nipple during suckling. Oxytocin has also been shown to spike in both mothers and infants when engaging in comforting interactions, such as skin-to-skin contact, strengthening the bond between the two. Romantic and sexual rapports are additionally associated with relatively high productions of this hormone. According to Feldman’s model, the convergence and integration of the dopamine and oxytocin systems at the level of a key subcortical structure known as the striatum is what confers incentive salience to various interpersonal bonding behaviours. Essentially, the synergy between these two signalling pathways is what makes affectionate interactions psychologically gratifying, thus driving individuals to seek them out for their rewarding effects.

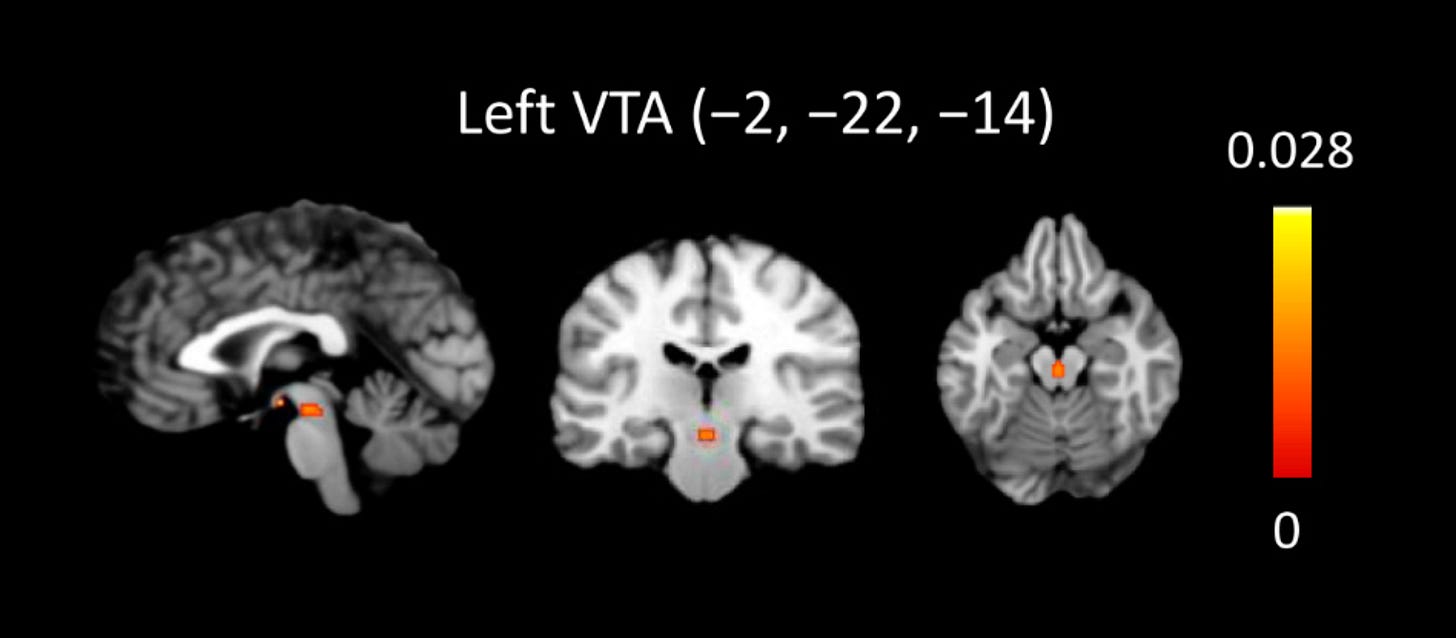

In a meta-analysis conducted by Shih et al. (2022), the researchers aimed to identify unique and shared patterns of cortical activation in two varieties of love: maternal and passionate. Conducting a quantitative assessment of 29 peer-reviewed articles, including 12 neuroimaging studies about maternal love and another 9 pertaining to passionate love, numbering a total of 169 activation foci, the authors ascertained the presence of both idiosyncratic and common cortical signatures for the two types of affection. While maternal love preferentially engaged the left ventral tegmental area (VTA), right thalamus, left substantia nigra, and left putamen, passionate love activated the bilateral VTA instead. Across the two forms of bonding, only the left VTA showed significant co-activation. Interestingly, contrasting maternal and passionate love yielded no finding, except for when the level of stringency in the statistical threshold was relaxed, whereby maternal love was found to recruit the left putamen more so than passionate love. The VTA acts as hub in the dopaminergic mesolimbic pathway, secreting dopamine into the nucleus accumbens of the ventral striatum, a process associated with the subjective high following substance use, the hedonistic feeling that accompanies sexual intercourse, or the satisfaction derived from consuming delicious foods. As such, it is a potent modular of pleasure and reward. While the authors did not report activations for the hypothalamus or caudate nucleus in the result section of their paper, they nonetheless claimed that involvement of these regions in maternal love indicates oxytocinergic contributions that are in accordance with the Neurobiology of Human Attachments Model. Overall, they concluded that while each variety of love differentially recruits the affective and motivational systems of the brain, both are anchored to a core evolutionary substratum in the mid-brain consisting of the VTA.

Until very recently, the neuroscience of affection had almost exclusively focused on the aforementioned forms of love, that is, maternal and passionate—or romantic. To offer a wider scope of how the brain sustains human bonding, Rinne et al. (2024) aspired to map out its functional involvement in the processing of six different objects of love, including romantic partners, children, friends, pets, as well as strangers and even nature. Using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) to measure cortical activity in 55 participants, the researchers studied the response of the brain when short stories meant to elicit feelings of love were read to the subjects inside the scanner.

The following is a list of short story exemplars narrated for each object of love.

Partner:

You are in the laundry room with your partner. They are loading the washer with laundry, and suddenly you remember what a lovely person your partner is. You feel love for them.

Child:

Your child runs to you joyful on a sunny meadow. You smile together and the sunrays flicker on their face. You feel love for your child.

Friend:

You need help moving house and you call your friend. They promise to of course come to help out, and soon you are lifting cardboard boxes together in a van. In the middle of the ordinary situation you feel love for your friend.

Pet:

You are in a park playing with your dog. You toss a stick for the dog and it retrieves it enthusiastically wagging its tail. You love your dog.

Stranger:

You see an old woman on the street carrying heavy grocery bags. You help her by carrying one of the bags to her home door one block away. The old woman is grateful, and you feel love for her.

Nature:

You are in the archipelago at the seaside. The blue waves ripple over the coastal stones, a crooked pine rises next to you, and there are white fluffy clouds here and there in the sky. You love nature.

A non-love related neutral condition was also included in the experiment to serve as a baseline for cortical measurements:

You are on the bus going home. Through the window of the bus one can see houses, cars, and people walking on the street. The view is quite ordinary.

Findings showed that neural activity associated with feelings of love varied depending on the object of affection. For example, love for other people engaged brain regions linked to social cognition—such as the temporoparietal junction and midline cortical structures—to a greater extent than love for pets or nature. Among pet owners, love for domestic animals triggered these areas to a significantly higher degree than in individuals who do not have pets. Additionally, interpersonal affection showed stronger and more extensive activation in the brain’s reward system compared to love for strangers, pets, or nature. Taken together, these observations paint an interesting picture, whereby the experience of attachment is marked by widespread patterns of cortical activation that vary as a function of the affection target. The authors suggested that love can be thought of as a multidimensional construct, with parental and romantic bonds constituting archetypical instances heavily rooted in biology, with other forms—such as love of animals or nature—representing examples that may be more socioculturally driven.

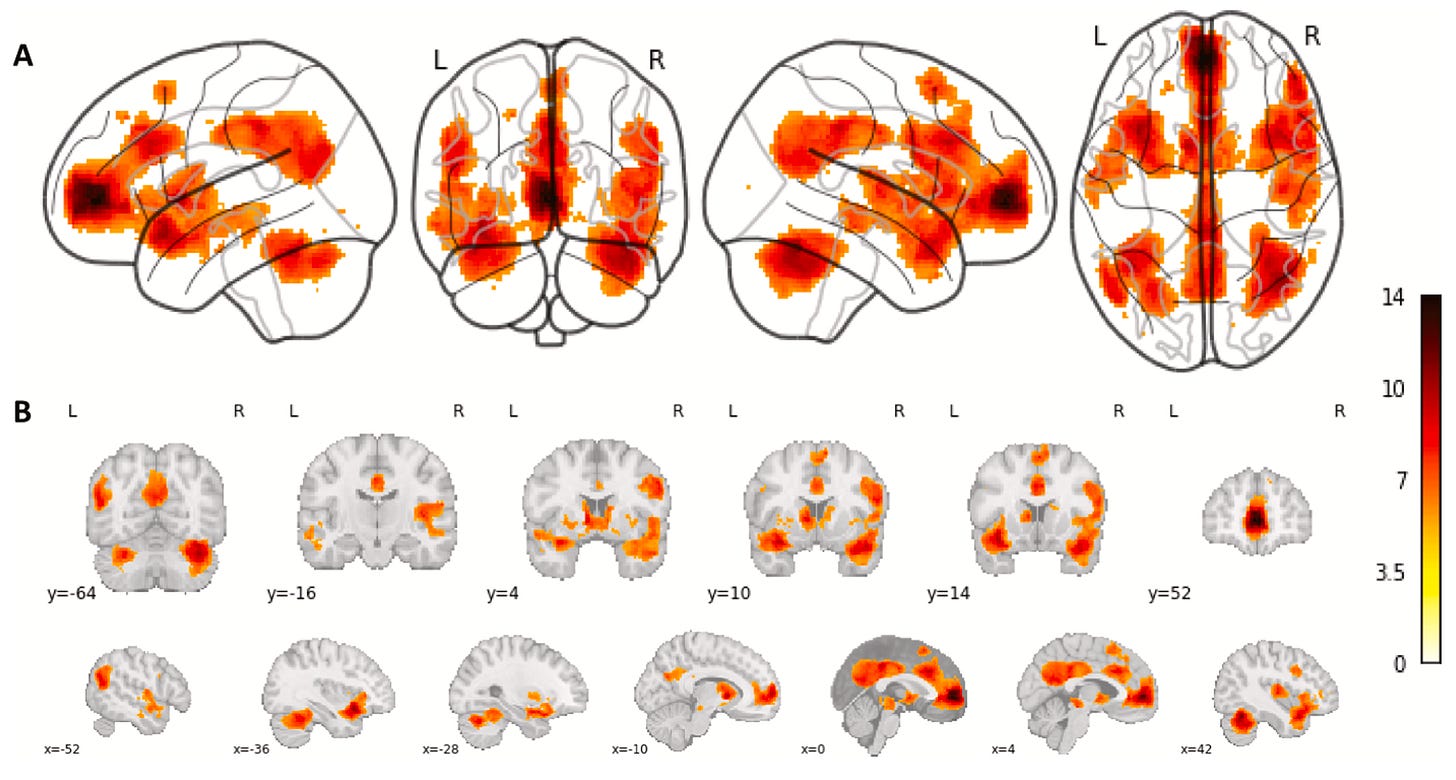

To overcome pervious limitations that had bogged down comprehensive evaluations of the neural circuitry of human bonding, Bortolini et al. (2024) conducted a meta-analysis of 79 fMRI studies with a total of 2,384 individuals. In addition to enhanced statistical power, the study also incorporated robustness measures to validate findings. Overall, it included 26 studies that used positive visual stimuli relating to own babies, 19 pertaining to friends, 14 associated with romantic partners, 10 involving non-child kin, and another 10 comprising auditory stimuli of own child’s cries—with one of these using both cries and pictures. Results showed extensive co-activations across regions of the brain implicated in diverse functions relevant to reward, motivation, social cognition, and salience detection, including clusters of finding in the inferior frontal gyrus, striatum, basal forebrain, amygdala, anterior insula, and anterior cingulate cortex. Above all, this meta-analysis elucidated the complexity of the functional neurocircuitry of human affection and affiliation, revealing the integration of cognitive systems spanning the mid-brain, forebrain, and higher executive areas.

The neuroscience of human attachment, while still in its nascency, has so far demonstrated that love is a multifaceted phenomenon, unsurprisingly. Cupid’s fingerprints can be found all over the brain as evidenced by widespread contributions from key cortical and subcortical actors within the basal ganglia, limbic system, and higher isocortical networks, with important neuromodulation from the dopaminergic and oxytocinergic systems. So to answer Haddaway’s lyrical question mentioned at the start of this article, I would propose the following working definition for what love is: Love is a subjective experience marked by psychological gratification when affective bonds are formed and strengthened between sentient beings, requiring the optimal integration of neurological systems spanning multiple scales of organization. Since I recognize just how technical and dry my neuroscientific interpretation may sound, I have compiled a short list of poetic characterizations of love spanning over 4,000 years of literary traditions across the world.

Would that you may find something to tickle your fancy in the following chronologically assorted selection of love-inspired quotes.

The Love Song of Shu-Sin (c. 2,000 BCE)

You, because you love me,

Give me pray of your caresses,

My lord god, my lord protector,

My Shu-Sin, who gladdens Enlil’s heart,

Give my pray of your caresses.

Symposium by Plato (c. 385 BCE)

Love is born into every human being; it calls back the halves of our original nature together; it tries to make one out of two and heal the wound of human nature.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare (c. 1595/1596)

Love looks not with the eyes but with the mind;

And therefore is winged Cupid painted blind.

Nor hath Love’s mind of any judgment taste.

Wings, and no eyes, figure unheedy haste.

And therefore is Love said to be a child

Because in choice he is so oft beguiled.

Mem u Zîn by Ehmedê Xanî (c. 1694/1695)

You, sunrise, have a fire whose flame is visible; I, too, as sunset, have this fire, but no one sees it […] But whether morning, evening, day, or depth of night, It is my lot to be consumed throughout by burning.

Notre-Dame de Paris. 1482 by Victor Hugo (1831)

Car pour une mère qui a perdu son enfant, c’est toujours le premier jour. Cette douleur-là ne vieillit pas. Les habits de deuil ont beau s’user et blanchir, le coeur reste noir.

White Nights by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1848)

I don’t know how to be silent when my heart is speaking. Well, never mind… Believe me, not one woman, never, never! No acquaintance of any sort! And I do nothing but dream every day that at last I shall meet some one. Oh, if only you knew how often I have been in love in that way…

Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche (1883–1892)

True, we love life, not because we are used to living, but because we are used to loving. There is always some madness in love. But there is also always some reason in madness.

References

A Midsummer Night’s Dream - Entire Play | Folger Shakespeare Library. (n.d.). Folger. https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/a-midsummer-nights-dream/read/

Bortolini, T., Laport, M. C., Latgé-Tovar, S., Fischer, R., Zahn, R., de Oliveira-Souza, R., & Moll, J. (2024). The extended neural architecture of human attachment: an fMRI coordinate-based meta-analysis of affiliative studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 159, 105584.

Feldman, R. (2017). The neurobiology of human attachments. Trends in cognitive sciences, 21(2), 80-99.

Ḫānī, A., Omar, F. F., Cohen, M. (2018). Mem U Zîn: A Classic Kurdish Epic from the 17th Century. Institut für Kurdische Studien.

Harvard Health. (2023, June 13). Oxytocin: The love hormone. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/oxytocin-the-love-hormone

Hugo, V. (2009). Notre-Dame de Paris. 1482. Éditions Gallimard.

Mark, J. J., & TangLung. (2025). The world’s oldest love poem. World History Encyclopedia. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/750/the-worlds-oldest-love-poem/

Negri, P. (Ed.). (2003). Great Russian Short Stories. Dover Publications, Inc.

Nietzsche, F., & Kaufmann, W. (1995). Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book For All And None. Modern Library.

Plato, Nehamas, A., & Woodruff, P. (1989). Symposium. Alexander Nehamas & Paul Woodruff.

Rinne, P., Lahnakoski, J. M., Saarimäki, H., Tavast, M., Sams, M., & Henriksson, L. (2024). Six types of loves differentially recruit reward and social cognition brain areas. Cerebral Cortex, 34(8), bhae331.

Shih, H. C., Kuo, M. E., Wu, C. W., Chao, Y. P., Huang, H. W., & Huang, C. M. (2022). The neurobiological basis of love: a meta-analysis of human functional neuroimaging studies of maternal and passionate love. Brain Sciences, 12(7), 830.