Ghost in the (Tolman-Eichenbaum) Machine

The hippocampal-entorhinal system as the cartographer of consciousness

Over and over again men are blinded by too violent motivations and too intense frustrations into blind and unintelligent and in the end desperately dangerous hates of outsiders. And the expression of these their displaced hates ranges all the way from discrimination against minorities to world conflagrations. What in the name of Heaven and Psychology can we do about it? My only answer is to preach again the virtues of reason—of, that is, broad cognitive maps.

~ Edward Tolman — Cognitive maps in rats and men (1948)

Why should you subscribe to ZAGROSCIENCE?

If you’re interested in hardcore neuroscience with an artistic flair, then you’ll enjoy ZAGROSCIENCE, which comprises an expanding library that includes audiovisual and written/narrated pieces on memory, consciousness, psychedelics, epilepsy, addiction, and much more. I’m also launching a new podcast series called The Abstract, where I’ll be interviewing leading experts in the field of brain research—some of whom are professional colleagues of mine. Valued patrons of ZAGROSCIENCE will be able to submit questions in written, audio, or video format, which I will curate and share on the show with my guests.

Why should you care about what I have to say about neuroscience?

I’m a cognitive neuroscientist who obtained his PhD at McGill University in 2024, specializing in memory and consciousness, with years of research experience at the Montreal Neurological Institute (aka, The Neuro) and over 25 (and counting) peer-reviewed publications in top scientific journals (i.e., Nature Neuroscience, Cerebral Cortex, Brain, Neuroimage, etc.). Here’s a PubMed link to my scholarly work (Tavakol is the surname under which I publish):

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=shahin%20tavakol%5BAuthor%5D&sort=fauth

On top of all that, I like to think that my writing is clear and engaging as I enjoy mixing in relevant themes from disciplines other than neuroscience (i.e., philosophy, literature, history, mythology, etc.).

Why should you read this particular article?

Factorization, conjunction, and path integration are believed to underlie how your brain makes sense of the world. So by understanding how these processes unfold inside your brain, the world around you might just become a little more sensible.

WHAT IS FACTORIZATION?

Consider the mathematical expression:

Since A is the common factor between AB and AC, we can “pull it out”:

This process, known as factorization, retains the underlying information, such that:

So why bother rewriting an expression in its factorized form if the content stays the same? The truth is, it adds information about information (or meta-information, if you prefer). Far from being a mathematical exercise in futility, factorization is a way of simplifying expressions, making it possible to extract general patterns across complex formulae that reduce complexity and streamline arithmetic computation.

Related mathematical and geometric operations are believed to be at the core of automatic mental processes that shape our lives. In the current issue of ZAGROSCIENCE, we will explore a prominent computational model of human cognition known as the Tolman-Eichenbaum Machine, which replicates three key operational features of the hippocampal-entorhinal system: factorization, conjunction, and path integration.

WHERE DOES THE NAME TOLMAN-EICHENBAUM COME FROM?

In 1948, Edward Tolman conducted two rodent experiments that ushered in the modern age of neuroscience. In the first one, rats trained to reach a food box inside a maze adapted their path finding behaviour when the contraption was altered, suggesting that they were using a mental representation of their environment for navigation. In the second experiment, rats trained in a T-maze to go left or right continued to follow the same direction even when the set was flipped, indicating that food target was not the only factor responsible for wayfinding. Taken together, Tolman argued that his findings showed that rodents can form a mental map of their surroundings, which he dubbed the cognitive map.

Many years later in 1993, Howard Eichenbaum and another colleague proposed the relational memory theory, which described the functional role of the hippocampus and associated areas as a relational system that binds multisensory information. This concept led Eichenbaum to argue that previously established hippocampal place cells, which were shown to fire in response to unique locations in a given environment, should instead be rebranded as relational cells, given their involvement in a wider scope of associative cognitive processes.

The Tolman-Eichenbaum Machine, thus, borrows its name from these two pioneers who advanced our understanding of spatial/relational brain-behaviour mechanisms.

Note: For more information on Tolman, Eichenbaum, cognitive maps, relational memory, and my own contributions to the field, see my inaugural essay on Substack titled Of Mice and Men - A Primer on the Neuroscience of Memory:

Of Mice and Men

Before the 1940s, behaviorism dominated psychology. This theory held that behavior could be explained by external stimuli and responses, without considering inner brain processes. Born from the need for scientific rigor in studying human nature, behaviorism brought experimentation and insights into learned behaviors, such as Pavlov’s classical condition…

WHAT IS THE TOLMAN-EICHENBAUM MACHINE?

Proposed by Whittington et al., (2020), the Tolman-Eichenbaum Machine (henceforth, TEM) is a mechanistic framework that explains your brain’s capacity to deconstruct, store, and manipulate the complex associations between the constituent elements of consciousness. At its core, TEM is modelled on the specialized neurons inside the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex that allow us to flexibly interact with and navigate the physical, social, and abstract domains of our lives.

WHAT IS THE HIPPOCAMPAL-ENTORHINAL SYSTEM

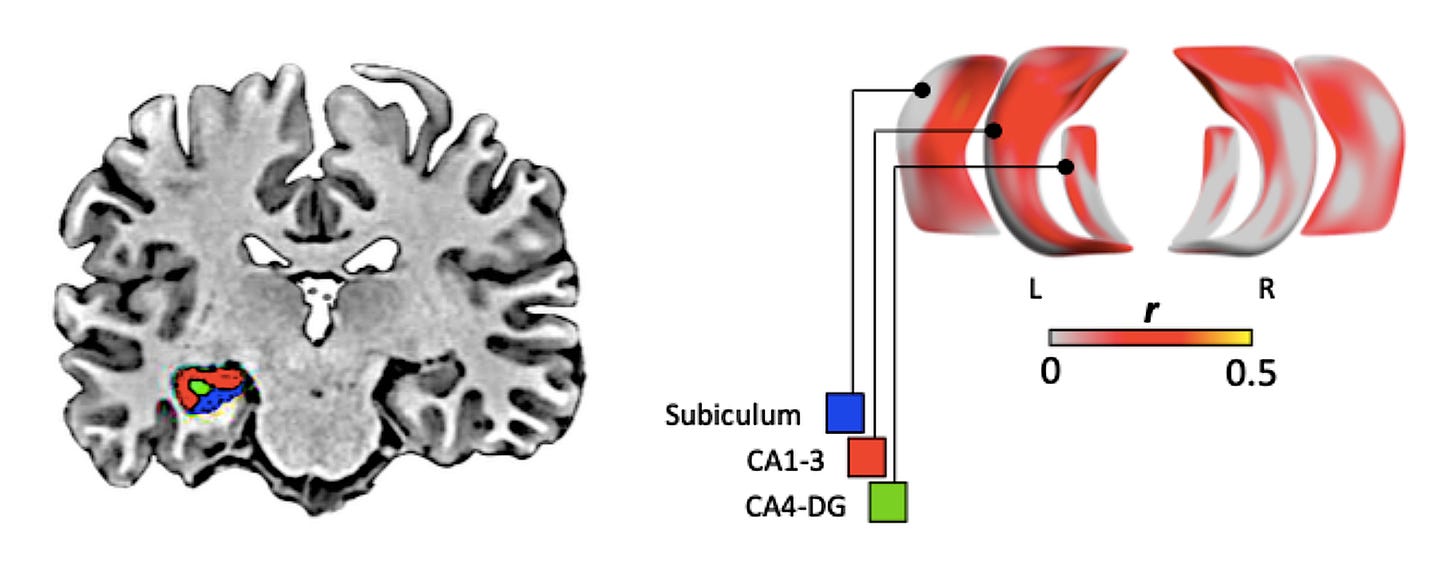

The hippocampus (from Greek hippos ‘horse’ + kampos ‘sea monster’) is a seahorse-shaped structure within the three-layered allocortex inside the medial temporal lobe (MTL) known to play a major role in memory, emotion, and general cognition. It is composed of several subregional structures known as subfields, including the dentate gyrus (DG), cornu ammonis (CA) 1-4, and subiculum.

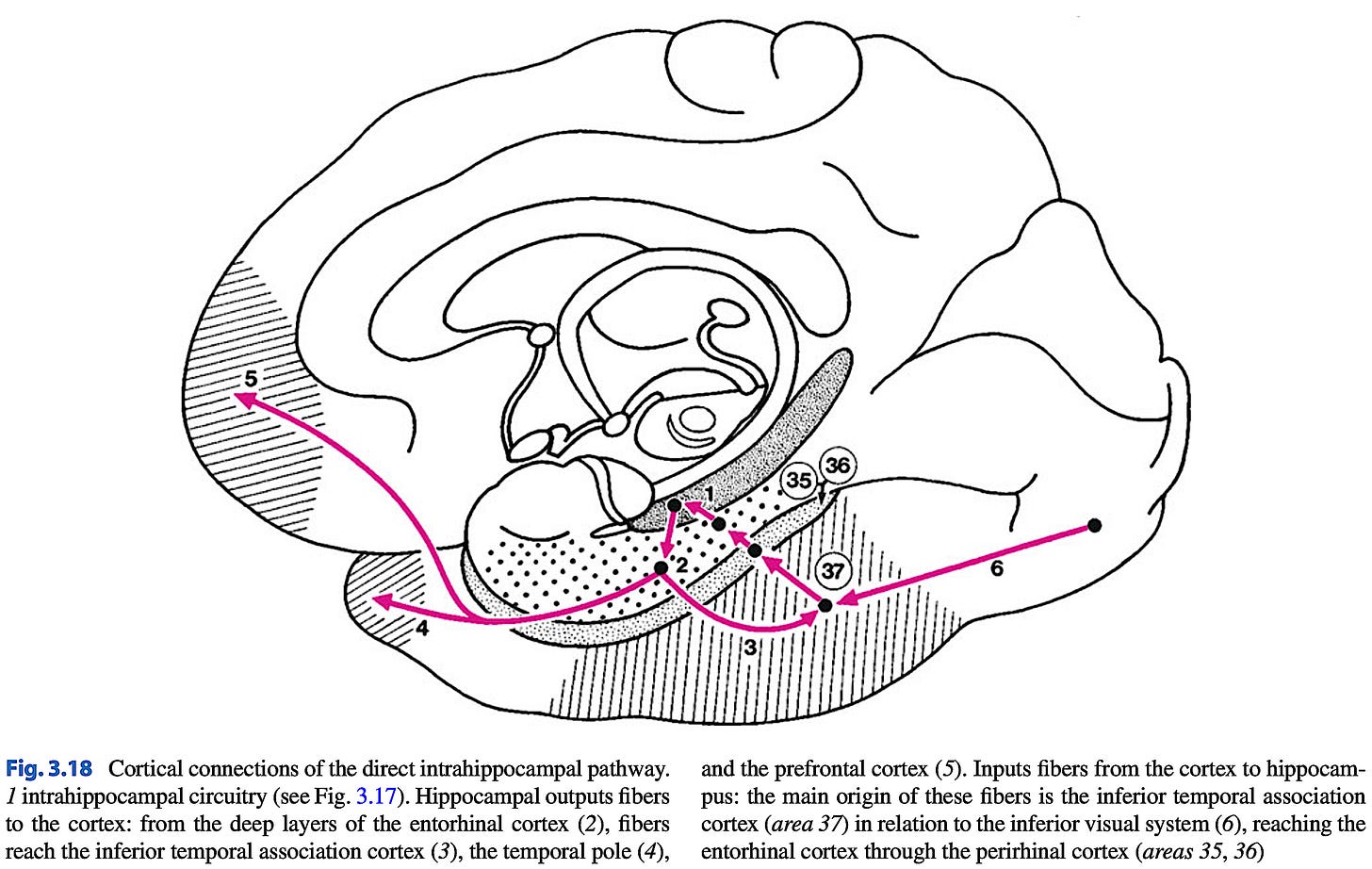

The entorhinal cortex (EC)—also part of the MTL—is immediately adjacent to the hippocampus, but situated in the six-layered isocortex (or neocortex). It represents the primary neocortical source of input/output to the hippocampus. Together, these structures form the hippocampal-entorhinal system, a neural complex that sustains relational memory across multiple sensory modalities.

WHAT SPECIALIZED CELLS ARE INVOLVED IN TEM?

Place cells (or relational cells) are hippocampal neurons that fire in response to a specific spatial location, called the place field. These were originally observed in rats with direct electrophysiological recordings of the dorsal CA1 subfield (O’Keefe & Dostrovsky, 1971) and later validated in humans using intracranial electrodes and virtual reality (VR) in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (Ekstrom et al., 2003).

Grid cells are found in the medial EC and are functionally similar to hippocampal place cells. However, while the hippocampal place field of a given place cell is confined to a single location in the immediate surroundings, the entorhinal grid field is instead marked by evenly spaced points that form a tessellating triangular pattern. First described in rodent experiments employing direct electrode recordings (Hafting et al., 2005), grid cells were later confirmed in drug-resistant epilepsy patients assessed with intracranial recordings while immersed in VR (Jacobs et al., 2013). Grid cells are also involved in path integration, which we will discuss later.

Border cells are sparsely distributed neurons in the medial EC that spike in response to proximal boundaries, such as walls and barriers. Initially recorded in freely moving rats navigating different enclosures, border cells have been proposed to anchor place and grid fields to the local environment by delineating its bounds (Solstad et al., 2008).

Object-vector cells, also found in the medial EC of foraging rodents, are tuned to the distance and direction of objects regardless of the rat’s orientation or the size/composition of the item (Høydal et al., 2019). Object-vector cells offer a cellular mechanism for mapping position in relation to physical landmarks.

cells in the lateral EC, unlike their medial EC counterparts, are responsive to non-spatial information. It has been shown in rodents that lateral EC cells play a role in the multisensory processing of objects, such as toys that vary in texture, shape, colour, and size (Deshmukh et al., 2011).

Note: Drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) is arguably the most well-established human model of memory impairment, serving as the focus of countless studies since the 1950s. Given that intracranial recordings are used to monitor disease progression in patients, DRE offers a unique opportunity to directly tap into the neural substrates of various forms of cognition, which explains the aforementioned discoveries of place and grid cells in humans. Read my article Cortical Wildfires for more information on this fascinating topic:

Cortical Wildfires

Ancient Mesopotamian archives are a treasure trove of humanity’s earliest and most iconic written documents. These texts cover a wide range of topics, including literature, mythology, history, law, and medicine. A 4,000-year-old Akkadian record describes the symptoms of a patient suffering from an intriguing ailment: “his neck turns left, his hands and …

HOW DO TEM CELLS PROCESS THE CONTENTS OF CONSCIOUSNESS?

A conscious experience can be construed as the product of two primary components: abstract associations between nondescript items and identifiable characteristics that make each item its own unique entity. Think, for example, of a family gathering. In this scenario, associations can be thought of as how each individual is related to everyone else while identifiable characteristics can be the red ribbon little Suzie is wearing around her hair or how grandpa is always clearing his throat when he is about to talk. Each circumstance comes with its own set of structural knowledge (i.e., family bonds) and sensory representations (i.e., identifiable features for each person).

According to the paper by Whittington et al., TEM posits that the specialized neurons of the hippocampal-entorhinal complex can factorize consciousness by extracting its underlying structural knowledge (via medial EC cells) and sensory information (via lateral EC cells). In a process known as conjunction, the hippocampus, which receives its main inputs from medial/lateral EC, can bind both components, forming what is called a conjunctive code, which can be stored in memory. This mechanism is key for learning via generalization, as conjunctive codes can be recalled and factorized anew to reveal latent structural knowledge that can be recombined with newly processed multisensory data.

As I have written in a previous work [https://zagroscience.substack.com/p/the-rabbit-marching-up-your-sleeve], your brain is constantly trying to make sense of the present by rehashing what it has previously learned—and sometimes, the clash between the two can play odd tricks on your mind…

WHAT ABOUT PATH INTEGRATION…WHAT IS THAT?

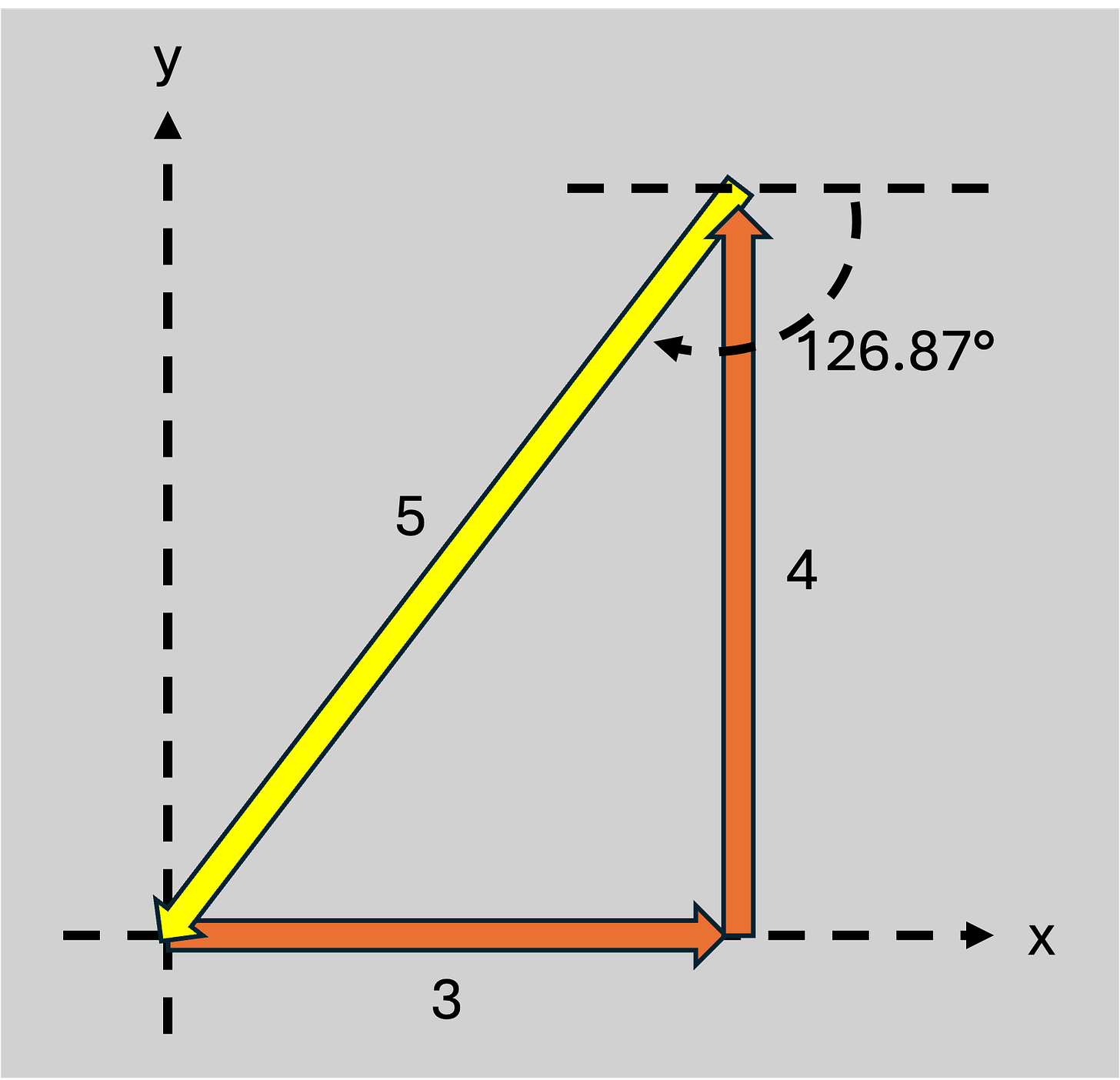

Let us assume that you live in a simple 2D Cartesian space at the origin (0,0). You move 3 paces right along the x-axis. Your current coordinates are (3,0). You then move 4 paces up along the y-axis. Your new location is (3,4). Path integration is knowing that to get back to the origin in one straight line, you must traverse 5 paces at 126.87° clockwise. From a cognitive neuroscience perspective, path integration is an incidental functional feature of the hippocampal-entorhinal system to implicitly compute the opposite of the resultant displacement vector (i.e., 5 paces at 126.87° clockwise) based on the individual component vectors (i.e., 3 paces right along the x-axis + 4 paces up along the y-axis). As you will find out, your brain can apply path integration to solve relational problems beyond the scope of spatial navigation…

WHAT DID WHITTINGTON ET AL., (2020) FIND?

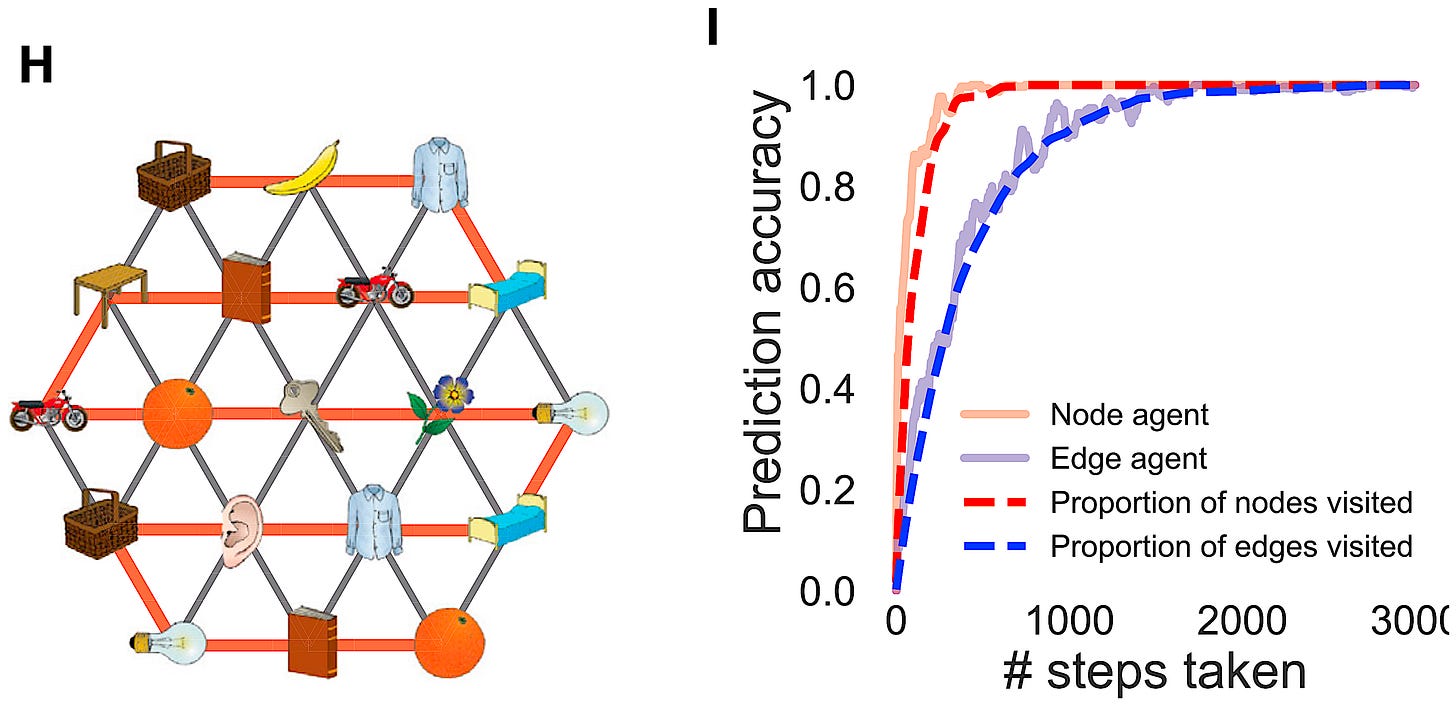

The authors developed an artificial neural network modelled after the principles of information factorization, conjunction, and path integration. They trained and tested their model on a number of graphs with different structural and idiosyncratic properties, where the artificial agent predicted the next item in a sequence of probabilistic transitions between nodes [note: in graph theory, a graph is a network comprised of nodes connected via edges]. Results from simulations showed that their machine learning algorithm reached 100% accuracy in item prediction either by sampling all nodes alone (i.e., node agent) or all nodes and edges together (i.e., edge agent). Interestingly, the node agent achieved peak performance much quicker than its counterpart. Consider this figure from Whittington et al.:

What the figure above shows is how a node agent that visits all nodes—but only a fraction of all edges (i.e., 18/42 or ~43%)—can learn the structural scaffolding of the graph and attain perfect prediction accuracy in a fraction of the time (measured here in network steps) than an edge node that must sample all connections.

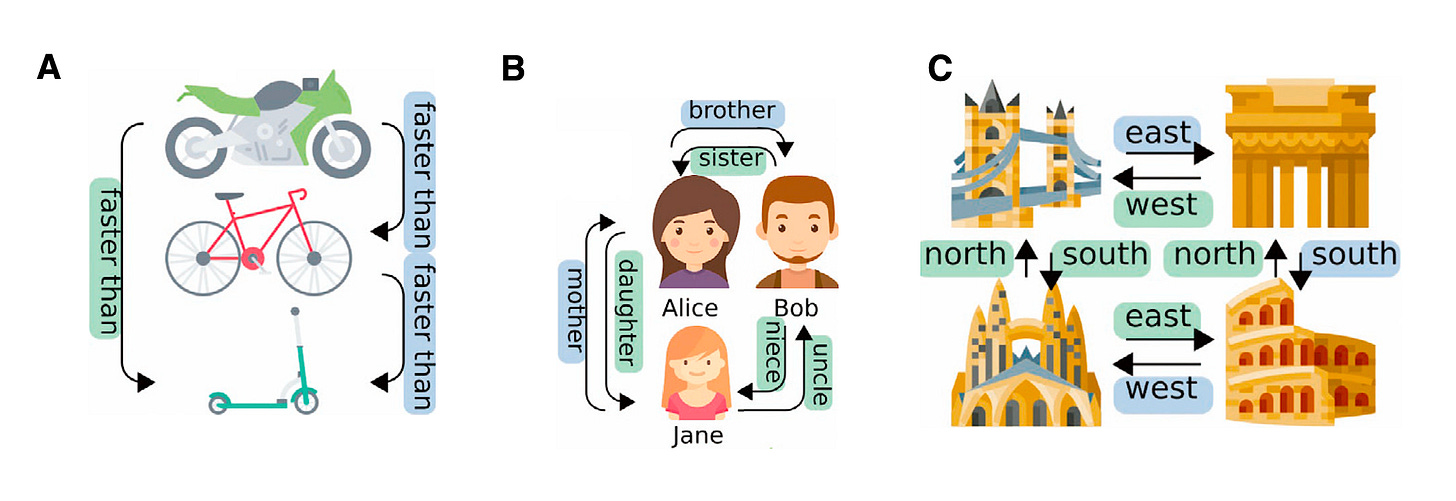

For the node agent, path integration is how the model learns to fill in the missing links (i.e., edges not sampled). What is noteworthy is that the algorithm can perform path integration regardless of whether the graph represents movements in physical space or conceptual associations in abstract space. In fact, so long as there is an intrinsic relational structure to it, the graph can schematize just about any feature space. Take a look at the following figures from the same paper:

The figure above displays three different relational schemes that showcase transitive (A), social (B), and 2D directional (C) connections. Given enough trials, the node agent will learn the latent structure of each graph and perform path integration to infer previously unseen edges. For instance, the associations in (A) show that the motorcycle is faster than the bicycle, which is faster than the scooter. Learning these links enables the model to determine that the motorcycle is faster than the scooter, even though it has not explicitly encoded this information during training. Similarly in (B), learning that Bob is Alice’s brother, and Alice is Jane’s mother, allows the algorithm to infer that Jane is Bob’s niece. Regardless of the nature of relations (i.e., transitive, social, or directional) or the identity of node objects (i.e., modes of transportation, humans, or landmark structures), the TEM neural network can flexibly manipulate information through factorization, conjunction, and path integration to learn novelty, recall associations, and merge old blueprints with new sensory stimuli, driving flexible behaviours that eventually meet the standards of peak performance.

WHAT IS THE TAKE-HOME MESSAGE?

The Tolman-Eichenbaum Machine (TEM), proposed by Whittington et al., (2020) and named after two pioneers who advanced our understanding of spatial/relational mechanisms, is a mechanistic model designed to explain your brain’s capacity to decompose, store, and manipulate the complex associations that constitute the contents of consciousness. This paradigm is based on the specialized neurons within the hippocampal-entorhinal system, an integrated neural complex that sustains relational memory across various sensory modalities. The system is believed to employ factorization to extract underlying structural knowledge—via medial EC cells—and sensory information—via lateral EC cells—from experience. The hippocampus then performs conjunction to bind these components into a storable conjunctive code. Furthermore, experiments utilizing an artificial neural network modelled on TEM demonstrated how path integration can infer previously unseen connections, enabling the TEM algorithm to flexibly manipulate information regardless of whether the context involves spatial or nonspatial associations.

ONE LAST QUESTION: WHERE IS THE GHOST IN THE MACHINE?

Contemporary neuroscience has little to say—if anything at all—about a mind that operates independently of the brain. As a physical science of the latter, it is, ultimately, bound to the atoms that make up the molecules that make up the neurons that make up the 3 pounds of tapioca pudding inside your skull. To the extent that the machine may be possessed, neuroscience can be regarded as the empirical framework that exorcises it, demystifying human nature in the process. It is said that nature, in general, reveals herself through the language of mathematics. The ghost in the Tolman-Eichenbaum Machine may just be, then, the sum-totality of mathematical operations inside the temporal lobes. And so, if human nature is reducible to the inner workings of your brain, then it stands to reason that these mechanisms spell out the universe.

Note: For a survey of modern scientific models of consciousness, reductionist vs. nonreductionist schools of thought, contemporary experimental paradigms, and the implications of memory as the basis for consciousness, I invite you to read the two essays I’ve listed below.

From Atoms to Qualia - The Neuroscience of Consciousness:

The rabbit marching up your sleeve - Mnemonic processing as an exegesis of consciousness:

FOLLOW THE RABBIT HOLE AND PICK YOUR POISON(S) FROM THIS LIST:

REFERENCES

Cohen, N. J., & Eichenbaum, H. (1993). Memory, amnesia, and the hippocampal system. MIT press.

Deshmukh, S. S., & Knierim, J. J. (2011). Representation of non-spatial and spatial information in the lateral entorhinal cortex. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 5, 69.

Duvernoy, H. M., Cattin, F., & Risold, P-Y. (2013). The human hippocampus: functional anatomy, vascularization and serial sections with MRI (4th ed.). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag

Eichenbaum, H., & Cohen, N. J. (2001). From Conditioning to Conscious Recollection: Memory Systems of the Brain. Oxford University Press.

Ekstrom, A. D., Kahana, M. J., Caplan, J. B., Fields, T. A., Isham, E. A., Newman, E. L., & Fried, I. (2003). Cellular networks underlying human spatial navigation. Nature, 425(6954), 184-188.

Hafting, T., Fyhn, M., Molden, S., Moser, M.-B., & Moser, E. I. (2005). Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature, 436(7052), 801-806.

Høydal, Ø. A., Skytøen, E. R., Andersson, S. O., Moser, M. B., & Moser, E. I. (2019). Object-vector coding in the medial entorhinal cortex. Nature, 568(7752), 400-404.

Jacobs, J., Weidemann, C. T., Miller, J. F., Solway, A., Burke, J. F., Wei, X.-X., Suthana, N., Sperling, M. R., Sharan, A. D., & Fried, I. (2013). Direct recordings of grid-like neuronal activity in human spatial navigation. Nature Neuroscience, 16(9), 1188-1190.

O’Keefe, J., & Dostrovsky, J. (1971). The hippocampus as a spatial map: preliminary evidence from unit activity in the freely-moving rat. Brain research.

Solstad, T., Boccara, C. N., Kropff, E., Moser, M. B., & Moser, E. I. (2008). Representation of geometric borders in the entorhinal cortex. Science, 322(5909), 1865-1868.

Tavakol, S., Li, Q., Royer, J., Vos de Wael, R., Larivière, S., Lowe, A., ... & Bernhardt, B. (2021). A structure–function substrate of memory for spatial configurations in medial and lateral temporal cortices. Cerebral Cortex, 31(7), 3213-3225.

Tolman, E. C. (1948). Cognitive maps in rats and men. Psychological review, 55(4), 189.

Whittington, J. C. R., Muller, T. H., Mark, S., Chen, G., Barry, C., Burgess, N., & Behrens, T. E. J. (2020). The Tolman-Eichenbaum machine: unifying space and relational memory through generalization in the hippocampal formation. Cell, 183(5), 1249-1263.

It's interesting how Tolman's message from 1948 on cognitive maps and countering 'hates of outsiders' remains so potent. His call for reason to build broad mental models for our society is esential. Thanks for highlighting this critical insight; it feels incredibly relevant for modern challenges.