New Year's resolutions work...if you put your ass into it

Scientific insights on how to maximize your chances of sticking to your objectives for 2026

REVISITING THE ODYSSEY

Back in July, I wrote an essay on the neural substrates of addiction in which I brought up Odysseus and his merciless 10-year-long voyage back to his home in Ithaca. I used his story as a metaphor to depict the drive and determination one needs to overcome substance use disorder, which, as I explained, consists of a vicious cycle of 3 phases that collectively hijack brain regions involved in executive function, motivation, reward, pleasure, and stress. As I was watching Christopher Nolan’s recent trailer of The Odyssey, it occurred to me that Homer’s eponymous epic, which is what the movie is based on, lends itself nicely to a discussion about a theme that is ubiquitous around this time of year: New Year’s resolutions. So, in this issue ZAGROSCIENCE, we bid 2025 farewell as we explore how you can optimize your resolve in 2026.

THE (NEURO)SCIENCE OF RESOLUTIONS

Overcoming the perils of the foreboding sea, the irresistible allure of Circe, and the unbreakable grip of the Cyclops—to say nothing of the furious anger of mighty Poseidon—requires the steadfast resolution of an unyielding mind at the helm of a stalwart body. And yet, not even the mighty Odysseus could’ve accomplished all his feats alone, which speaks to the necessity of adequate support for staying the course.

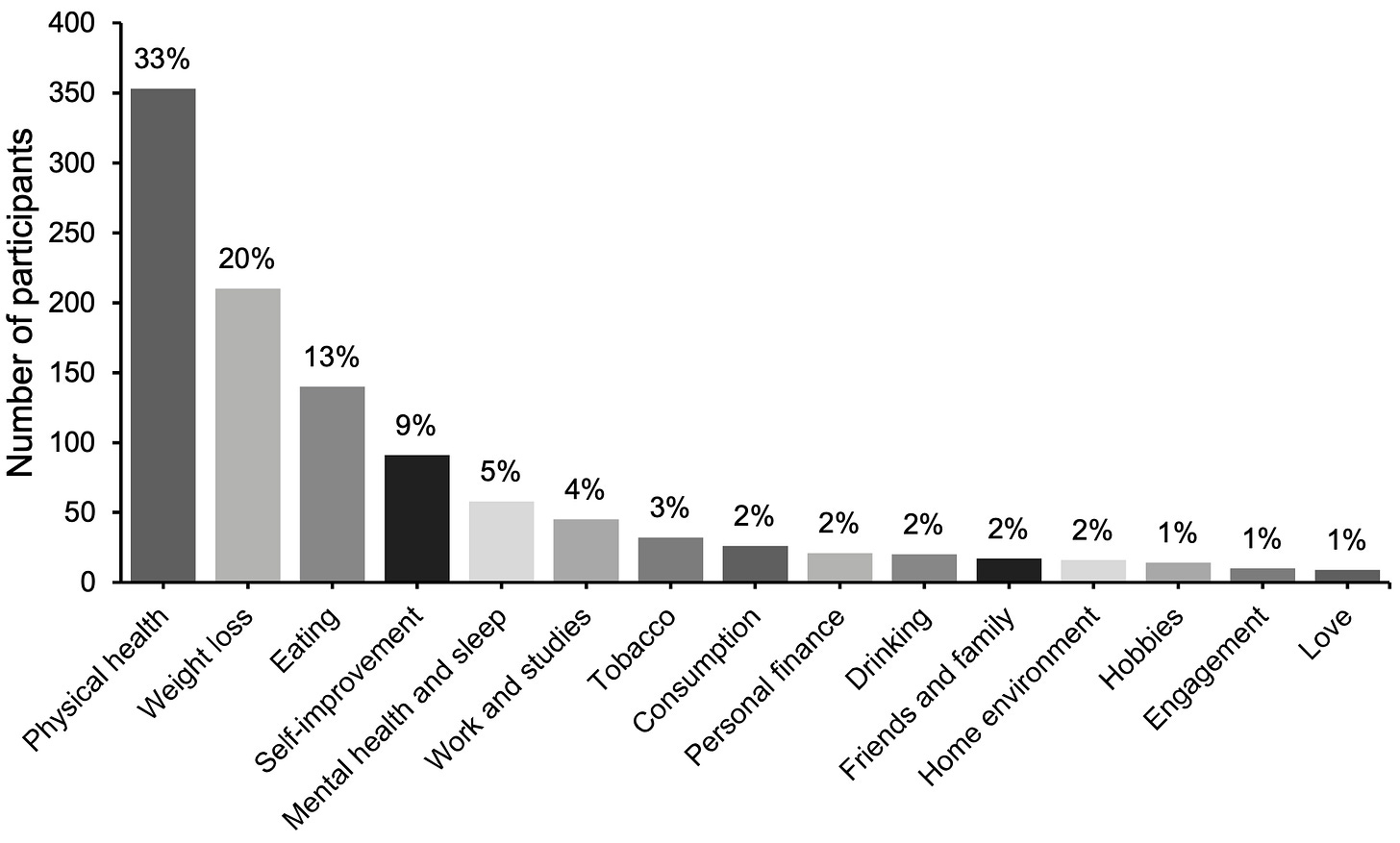

In 2020, Oscarsson and colleagues published one of the largest studies on New Year’s resolutions, investigating a sample of 1,066 participants randomized into 3 groups: active control (AC), some support (SS), and extended support (ES). The objective was to categorize different kinds of resolutions, evaluate the success rate of each, and establish the importance of support in adhering to one’s plans. The AC group received brief guidelines and 3 follow-ups throughout the year; the SS group was given social support instructions, 12 monthly follow-up assessments, and one email containing exercises and coping strategies; the ES group was provided specific goal instructions, interim objectives, 12 monthly follow-ups, and 4 emails with exercises. Overall, the top 3 resolutions that participants chose pertained to physical health (33%), weight loss (20%), and eating habits (13%), with a general success rate of 55% across all groups over the course of 1 year.

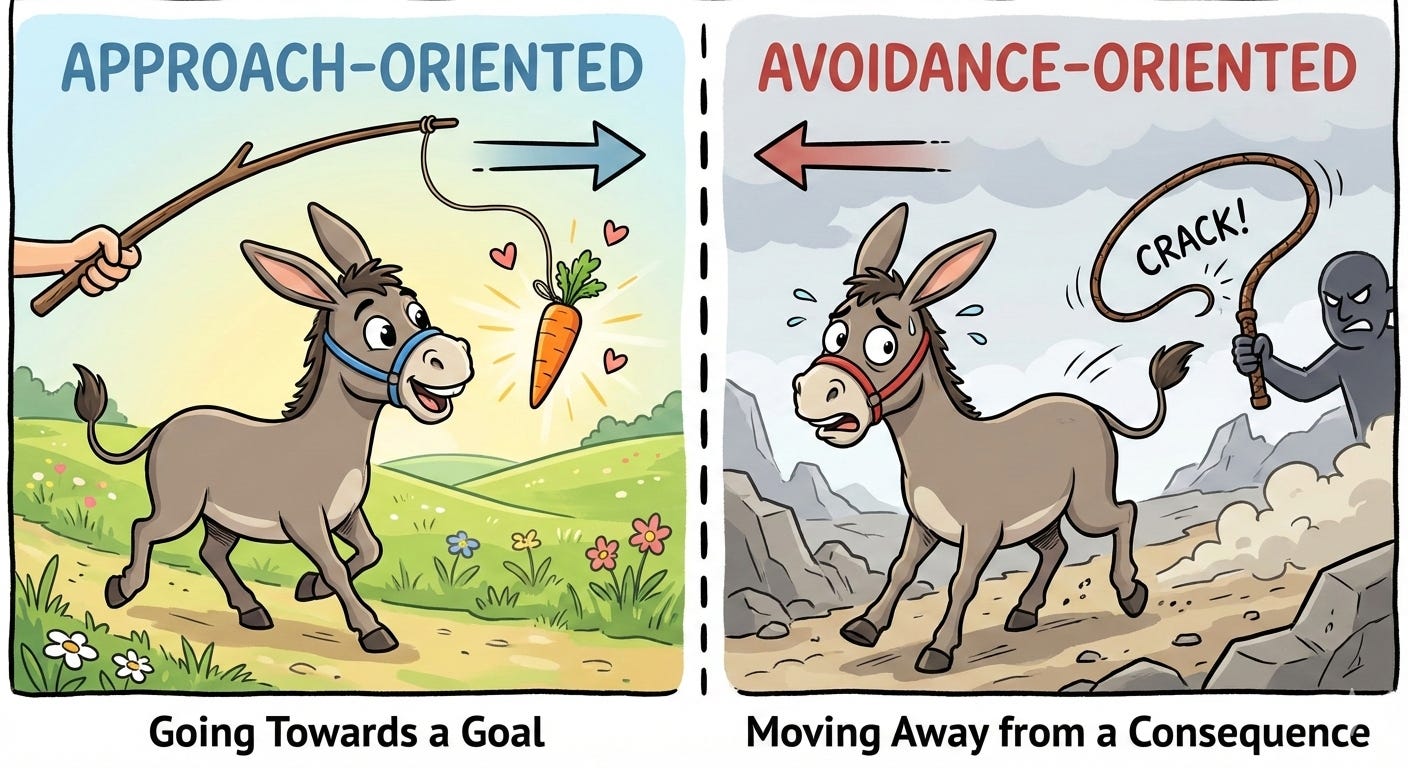

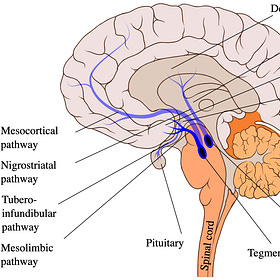

One major finding in this study was that approach-oriented goals showed higher rates of adherence than avoidance-oriented goals (58.9% vs. 47.1%). An approach-oriented objective is one in which you are actively trying to move towards a positive outcome, whereas in an avoidance-oriented paradigm, you are attempting to steer clear of a negative consequence. Approach-oriented strategies are neurally associated with networks linked to reward, positive emotions, and flexible control, whereas avoidance-oriented goals preferentially recruit brain systems involved with anxiety, vigilance, and cognitive control.

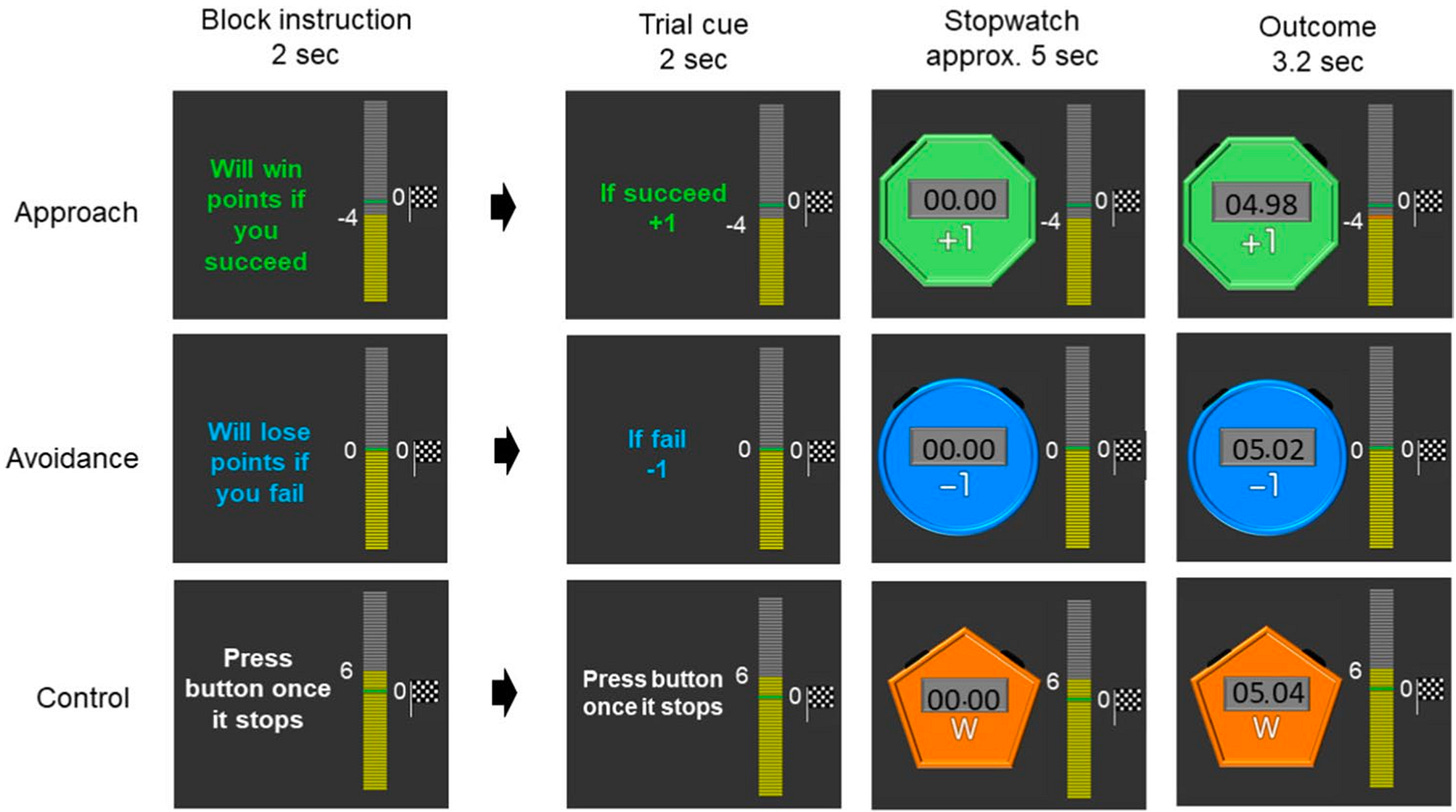

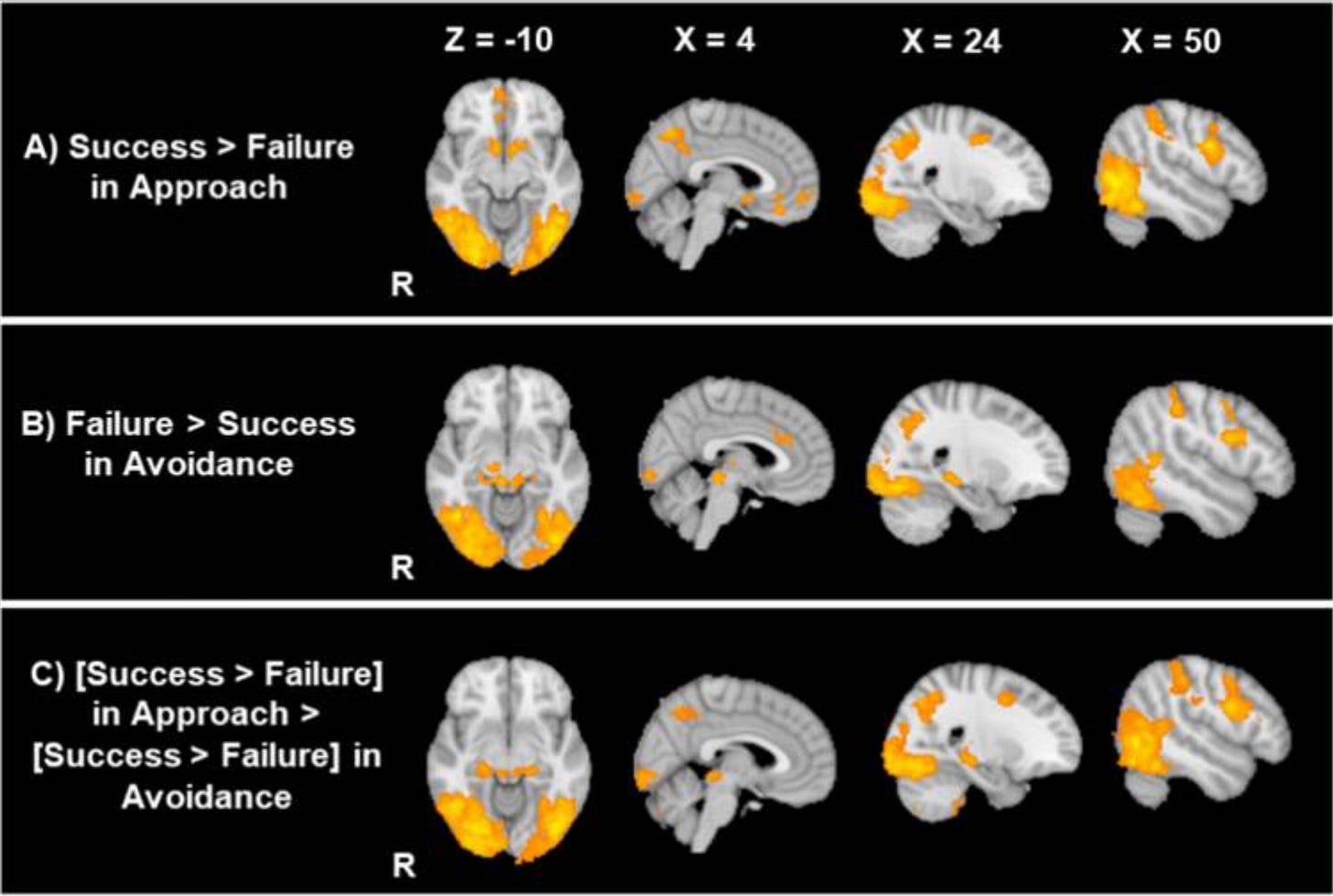

In a recent neuroimaging study (Sakaki et al., 2024), researchers examined how different objective-driven strategies for the same task can modulate the brain’s reward system, namely, the striatum and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). A total 20 young adults performed a stopwatch task while being scanned in the MRI machine. At each trial, participants had to pause a stopwatch via button press within 50 ms of the 5-second time point. Depending on whether or not the stopwatch was paused within the allotted time window, the trial was either deemed a success or a failure. To assess the effect of the subject’s motivational state of mind, participants completed the task in 3 separate blocks: in the approach block, they gained points for succeeding and lost nothing for failing; in the avoidance block, they lost points for failing and gained nothing for succeeding; in the control block, they simply watched the timer and pressed a button without gaining or losing points.

Univariate analysis was used to compare the different conditions while functional connectivity determined network associations during different goal states. Additionally, to compare the similarity of brain patterns across the different conditions, a multivariate technique known as representational similarity analysis (RSA) was performed. Behaviourally, participants reported relatively higher levels of excitement and engagement in the approach condition while exhibiting more anxiety and disappointment during avoidance. Intriguingly, regardless of emotional differences in the two conditions, the brain’s reward network showed comparable activity. Even so, neural signatures in the striatum and vmPFC were found to differentiate between approach and avoidance strategies, speaking to a fundamental distinction in how this neural circuitry processes them. What’s more, regions outside canonical reward areas showed different activation effects of success/failure between experimental conditions, with significant interactions in the lateral occipital gyrus, hippocampus, cerebellum, and brainstem. These brainwide variations may be an important piece of the puzzle in understanding why approach-oriented goals tend to feel more enjoyable, sustainable, and effective in driving behaviour than avoidance.

Another interesting result by Oscarsson et al., (2020) is the nonlinear relationship between support and resolution success rate. The report found that the SS cohort, which had received moderate support, saw significantly greater success in adherence to New Year’s resolutions than either the AC group—which had received almost no aid—or the ES group—which was given extensive and prolonged help. The authors suggested that too many goals and interim deadlines may actually increase the potential for failure. Indeed, clearly formulated time-sensitive objectives are a great way to recruit and mobilize your energy and cognitive resources, but too many of them within a relatively short period of time could end up backfiring by overburdening you with noise and redundancy.

The article also noted some encouraging secondary outcomes. Namely, participants who adhered to their resolutions throughout the year scored significantly higher in assessments of self-efficacy and subjective quality of life than those who gave up. Furthermore—and perhaps more importantly—regardless of whether or not their New Year’s resolutions were successful, participants generally showed a positive change in reducing procrastination, which speaks to the potential psychologically beneficial secondary effects of harnessing one’s motivation and drive irrespective of ultimate outcome.

TAKEAWAYS

Set realistic goals in which you are ideally moving towards a specific positive outcome. This approach will keep you motivated on the path ahead while possibly strengthening brain networks involved in feeling accomplished.

Keep track of your progress but don’t micromanage everything to the point where you overburden yourself with increased failure potential. There is a fine line here, which only you can identify for yourself.

If you falter, it’s ok—you’re only human. But try and resolve the root causes of your shortcomings. Triumphing over temporary setbacks along the way can actually make you more resilient against inertia post-failure, which is good!

Just like Odysseus, you need some support—not too much, but not too little either…perhaps a close confident who checks up on your progress once in a while or even a self-made memo that reminds you of the larger picture when you’re feeling down.

So whatever you set your sights on for 2026, whether it’s becoming more fit, eating healthier, or making millions of dollars with your Substack newsletter, don’t forget to make your resolution simple and clear so that it counts. And remember, you don’t need to become a beast of burden to put your ass into it!

Let me know if you value all the work I’ve done this year at ZAGROSCIENCE

Some relevant essays from the ZAGROSCIENCE vault.

Neurodivergence: A System-Level Account Of The Autistic Brain

“[T]he real mystery of absolute pitch is not why some people possess this ability, but instead why it is so rare.”

Unlocking New Abilities: Lessons From A Neuroscientist-Martial Artist

“Thou shalt not scathe thine neurones.”

If you’re into neuroscience (the real deal - not the cheap online fluff), check out my new podcast The Abstract, where I interview the women and men who are driving it forward.

The Abstract | Episode 1 | Dr Boris Bernhardt

Brain function: the interplay between local specialization and global integration

The Abstract | Episode 2 | Dr. Sara Larivière

Beyond the seizure epicentre: a network approach to temporal lobe epilepsy

REFERENCES

Oscarsson, M., Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., & Rozental, A. (2020). A large-scale experiment on New Year’s resolutions: Approach-oriented goals are more successful than avoidance-oriented goals. PLoS One, 15(12), e0234097.

Sakaki, M., Murayama, K., Izuma, K., Aoki, R., Yomogita, Y., Sugiura, A., Singhi, N., Matsumoto, M., & Matsumoto, K. (2024). Motivated with joy or anxiety: Does approach-avoidance goal framing elicit differential reward-network activation in the brain?. Cognitive, affective & behavioral neuroscience, 24(3), 469–490. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-024-01154-3