Unlocking New Abilities: Lessons From A Neuroscientist-Martial Artist

“Thou shalt not scathe thine neurones.”

~ The Unspoken Commandment

IRON SHARPENS IRON

I come from a strict mixed martial arts pedigree: gruelling sessions of conditioning, relentless drilling of technique, and hard bouts of grappling and sparring. When Sifu1 asks you to jump, your only thought is, “how high?” There is no room for physical fatigue or mental weakness—it’s full commitment to the here and now in body and mind, or nothing else. Mine is a tried and tested warrior’s paradigm in which iron sharpens iron. And yet, while 18-year-old me thrived in this hardened environment, 40-year-old me today can certainly impart a few words of wisdom on my younger self. So if you’re anything like 18-year-old me—indefatigable and single-minded but sometimes lacking perspective—strap yourself in, because in this issue of ZAGROSCIENCE, class is in session and the master is taking you to school!

NEUROBIOLOGICAL OVERVIEW

A recent review published in Brain Research by Gazerani (2025) frames skill learning as an iterative adjustment in cortical and subcortical circuits that minimizes prediction errors while maximizing reward. This process is similar to how machine learning algorithms reduce the cost (or loss) function, which includes making predictions, weighing these predictions against defined targets, and recalibrating system parameters to ensure that downstream predictions are closer to expected values. Inside the brain, this mechanism is sustained by a convergence of processes involving neuroplasticity (e.g., structural and functional reorganization), time-dependent consolidation, optimal cognitive load, and neuromodulation via signalling compounds like dopamine and norepinephrine.

![Goldberg (2022) [same caption as in source material] - When learning and performance demands exceed the available support and resources, students are likely to be overwhelmed and resort to survival mode (stress zone). When learning and performance demands are significantly lower than the available support and resources, students are likely to be under stimulated and resort to static mode (comfort zone). When learning and performance demands match the available support and resources, students are likely to be appropriately challenged and work within their zone of proximal development, which promotes neuroplasticity and growth (stretch zone). Goldberg (2022) [same caption as in source material] - When learning and performance demands exceed the available support and resources, students are likely to be overwhelmed and resort to survival mode (stress zone). When learning and performance demands are significantly lower than the available support and resources, students are likely to be under stimulated and resort to static mode (comfort zone). When learning and performance demands match the available support and resources, students are likely to be appropriately challenged and work within their zone of proximal development, which promotes neuroplasticity and growth (stretch zone).](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Y2So!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe0ab9052-d3a8-4807-b69e-dd3ced5e75d5_2754x1506.png)

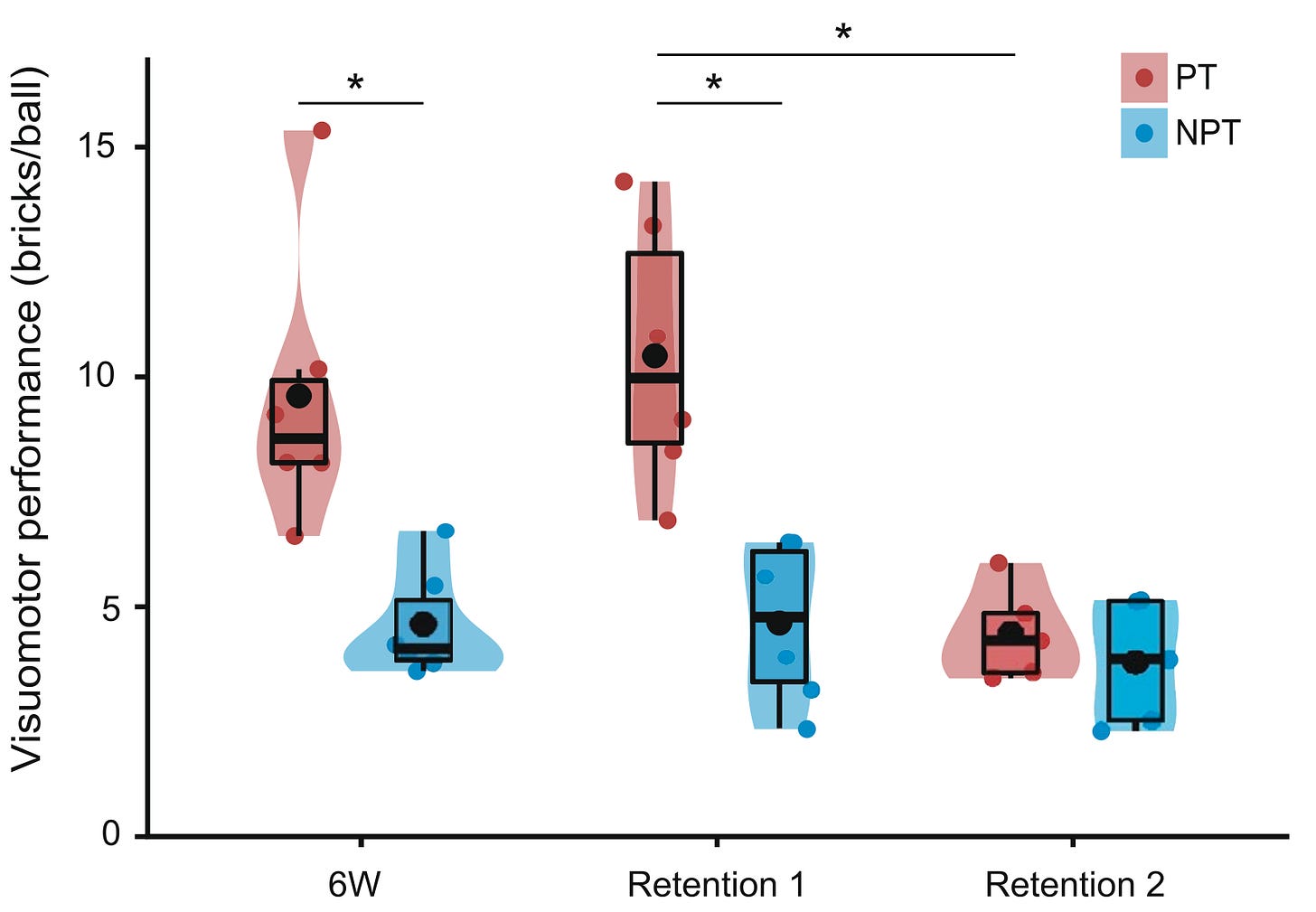

PROGRESSIVE COGNITIVE LOAD FOR OPTIMIZED SKILL ACQUISITION

In Christiansen et al., (2020), researchers compared two groups on a visuomotor task over the course of 6 weeks. In the progressive training (PT) cohort, training difficulty was continuously readjusted to match individual skill levels whereas it was held constant in the nonprogressive training (NPT) group. The study found that, on average, participants adhering to the PT regimen outperformed their NPT counterparts by a factor of 2, with associated heightened corticospinal excitability. Two additional retention reassessments were conducted after the original 6-week period. At retention 1, following 8 days of discontinued practice, group differences were replicated, showing that PT had maintained its performance advantage over NPT. However, when both cohorts were reappraised again after 14 months of no training, scores no longer differed, speaking to the importance of sustained practice in honing a skill. Nonetheless, the authors remarked that when it comes to learning, a regimen that offers gradually more challenging tasks dynamically tailored to the individual’s proficiency may be superior to one in which the challenge remains constant:

Our study demonstrates for the first time that an individually adjusted, progressive training protocol involving 6 weeks of visuomotor skill acquisition results in significantly better motor performance compared to a non-progressive skill learning protocol. Progressive training was also accompanied by pronounced increases in corticospinal excitability suggesting that continuous challenge during motor training drives corticospinal plasticity.

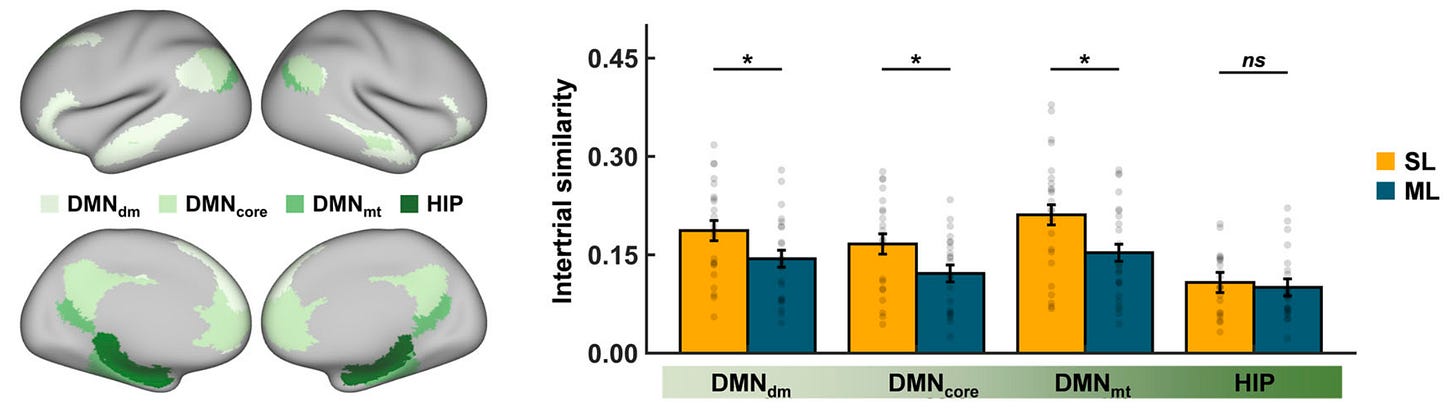

SPACING OUT SESSIONS FOR CONSOLIDATION

Time-dependent consolidation is when fleeting neural traces become integrated into longer-lasting memory circuits. A new study by Yang et al., (2025) found that spaced learning may be crucial for the formation of durable memories. Unlike mass learning, which is marked by cramming of information—over a relatively short period of time—spaced learning involves the distribution of study sessions over a longer timeframe. The researchers used a between-subject, day-based design where 48 participants were randomly allocated to either a 3-day spaced learning cohort or a 1-day massed learning group as they learned 60 picture-word pairs. Resting-state and task-based fMRI data were acquired during multiple delayed tests: immediately, after 1 week, and after 1 month. To examine neural integration and spontaneous memory replay, the study employed representational similarity analysis (RSA) in the hippocampus and regions of the default mode network (DMN), with complementary multivariate analytical techniques (e.g., multivoxel functional connectivity and multivariate pattern analysis). Memory performance was found to be significantly higher in the spaced learning cohort relative to the massed learning group in the 1-week and 1-month delayed tests, but not in the immediate test. Spaced learning was further associated with superior retention rates across both delays. Neural integration in the dorsal-medial and medial-temporal DMN at 1-month was linked to durable memory induced by spaced learning. Increased neural replay was additionally observed in the dorsal-medial DMN. Overall, the authors concluded that while the hippocampus is heavily involved in initial memory processing, time-dependent consolidation may occur as a result of enhanced integration in the neocortex rather than the hippocampus.

SLEEP FOR BRAIN RECALIBRATION

In 2021, Newbury et al. published a dual meta-analysis that examined the negative effects of acute sleep deprivation on memory both before and after learning (e.g., BL vs. AL), spanning 50 years of research (e.g., from 1970 to 2020). In the BL module, a total of 31 studies were quantitatively analyzed, yielding a medium-to-large detrimental effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.621, 95% CI [0.473, 0.769]), supporting the idea that sleep prepares the brain for new learning. In the AL module, 45 studies were examined, resulting in a smaller, albeit non-negligible, effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.277, 95% CI [0.177, 0.377]), indicating that sleep plays a role in the consolidation of newly learned information. Interestingly, the negative effects of sleep deprivation were more significant for procedural memory tasks (e.g., finger-tapping, visual discrimination, mirror tracing, etc.) compared to declarative tasks (e.g., word pairs, route learning, categorization, etc.). What’s more, this difference was more noticeable if testing occurred immediately after deprivation rather than after recovery sleep, pointing to a restorative effect of sleep following deprivation. Generally speaking, procedural memory taps into motor and/or visual processing, whereas declarative memory is primarily hippocampal-dependent. Procedural memories are believed to require immediate offline (e.g., sleep) consolidation as they are unlikely to rely on online (e.g., awake) hippocampal-neocortical dynamics. As for declarative memories, while they are incidentally encoded by the hippocampus during wakefulness, slow-wave sleep (SWS) is believed to support their strengthening and integration into the neocortex via repeated reactivation. In both cases, sleep ultimately plays an important factor.

MULTIMODAL LEARNING FOR MAXIMAL INTEGRATION

Multimodal enrichment is when complementary sensory and/or motor stimuli are incorporated into the learning process. Imagine you’re learning to taste and identify wines. In a unimodal paradigm, an instructor may simply have you taste the wine and then verbally describe its aroma (e.g., “This wine presents with an elegant bouquet of violets.“). A multimodal approach may, in addition to the verbal description (e.g., auditory stimulus), have you taste the wine (e.g., gustatory stimulus) and also smell a violet flower (e.g., olfactory stimulus) for cross-comparison. A review by Mathias & von Kriegstein (2023) integrated cognitive, neuroscientific, and computational approaches to shed light on the effectiveness of multimodal enrichment on skill acquisition, noting that it can drastically improve learning across multiple domains (e.g., vocabulary acquisition, reading, mathematics, etc.). The review found that behavioural benefits were associated with underlying cortical changes: sensory and motor areas exhibited crossmodal integration in response to enriched items during subsequent unimodal tasks. Findings supported the idea that multimodal enrichment contributes to enhanced multisensorial consolidation at the level of the brain, significantly reinforcing cortical representations that support learning and memory.

![Mathias & von Kriegstein (2023) [same caption as in source material] - (A) In this example, multisensory enrichment is used: birdsong is learned under two conditions. In an enriched learning condition, each song is paired with a picture of a specific bird species. In a non-enriched learning condition, each song is learned with no accompanying visual stimulus. (B) Following learning, enriched birdsongs are recognized faster and more accurately compared with non-enriched birdsongs (enrichment benefit). Multimodal and unimodal theories offer diverging theoretical accounts of enrichment benefits. (C) Cognitive theories. Multimodal theories propose that the recognition of a familiar birdsong can activate its corresponding picture, thereby facilitating the recognition of the birdsong. Unimodal theories propose that general cognitive mechanisms, such as greater attention or the processing of the meaning of an item rather than its surface-level features, during enriched learning, yield enhanced recognition of enriched birdsongs. (D) Neural theories. Multimodal theories come in two possible flavors: crossmodal and supramodal. During crossmodal processing, recognition of an auditory-only presented birdsong after visually enriched learning triggers responses within auditory brain regions (red circle) and crossmodally in visual brain regions (blue circle), which interact. By contrast, during supramodal processing, recognizing the visually enriched birdsong triggers responses within auditory brain regions and audiovisual convergence zones (black circle). According to unimodal theories, enriched birdsong is processed solely by auditory brain regions even after enriched learning. Theoretically, crossmodal, supramodal, and unimodal mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and could operate in parallel. Mathias & von Kriegstein (2023) [same caption as in source material] - (A) In this example, multisensory enrichment is used: birdsong is learned under two conditions. In an enriched learning condition, each song is paired with a picture of a specific bird species. In a non-enriched learning condition, each song is learned with no accompanying visual stimulus. (B) Following learning, enriched birdsongs are recognized faster and more accurately compared with non-enriched birdsongs (enrichment benefit). Multimodal and unimodal theories offer diverging theoretical accounts of enrichment benefits. (C) Cognitive theories. Multimodal theories propose that the recognition of a familiar birdsong can activate its corresponding picture, thereby facilitating the recognition of the birdsong. Unimodal theories propose that general cognitive mechanisms, such as greater attention or the processing of the meaning of an item rather than its surface-level features, during enriched learning, yield enhanced recognition of enriched birdsongs. (D) Neural theories. Multimodal theories come in two possible flavors: crossmodal and supramodal. During crossmodal processing, recognition of an auditory-only presented birdsong after visually enriched learning triggers responses within auditory brain regions (red circle) and crossmodally in visual brain regions (blue circle), which interact. By contrast, during supramodal processing, recognizing the visually enriched birdsong triggers responses within auditory brain regions and audiovisual convergence zones (black circle). According to unimodal theories, enriched birdsong is processed solely by auditory brain regions even after enriched learning. Theoretically, crossmodal, supramodal, and unimodal mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and could operate in parallel.](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!m3se!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F13a7f922-5f6b-4dc5-a08b-e55bde74c21e_1270x1706.png)

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Based on the latest in neuroscientific research, optimization of skill acquisition can be broken down into the 4 points:

individually-tailored progressive cognitive load to operate at optimal capacity (e.g., “stretch zone”)

spaced out sessions to enhance consolidation of new skills in between bouts

good quality sleep to promote skill/knowledge integration

multimodal enrichment learning to activate converging neural pathways

Implementing this multipronged approach when learning new abilities can maximize how quickly and reliably you can expand your arsenal of procedural and/or declarative expertise.

THE EDICT OF LONGEVITY

I remember Sifu telling me how he was in the best shape of his life in his mid-40s. As someone who is approaching this age range myself, I find the prospect of having my best years still ahead of me reinvigorating. Of course, I need to be proactive about it. Although I’m no longer training martial arts anywhere near the frequency and intensity I would like to be, I’ve taken up weightlifting in the last couple of years as a substitute. I have implicitly adhered to a semi-structured regimen that incorporates, where applicable, the 4 points mentioned earlier—although good sleep is not always easy to come by when you have a toddler at home… Nonetheless, while my cardiovascular fitness remains a work in progress, I have never been physically stronger than what I am now (see the video below where I deadlift 315 lbs [~143 kg] for 6 repetitions with relative ease).

In retrospect, the biggest piece of advice I’d give my younger self would be to ease off the full contact sparring. It goes without saying that minimizing concussive blows to the head is a good strategy for safeguarding the integrity of the primary organ responsible for learning. If your brain is compromised in the process of acquiring and honing a skillset, the process itself becomes compromised. In fact, I’m not convinced that full contact sparring is a necessary training paradigm even for pugilistic professionals like mixed martial artists and boxers. As discussed earlier, your brain thrives under optimal conditions of cognitive load: too little input, and it’s operating at subpar levels; too much, and it’s overburdened—and getting knocked unconscious is your brain’s way of spelling out “system overload!” Indeed, repetitive hard blows to the cranium serve no other purpose than to increase your likelihood of developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Imagine smashing your computer with a baseball bat in an attempt to update its software—it just makes no sense! But based on what neuroscience and martial arts have taught me, it’s an analogy that rings true with giving yourself brain damage while aspiring to sharpen your combat skills. In my opinion, more rounds of light sparring, technique drilling, reaction training, and mental imagery constitute a far more auspicious regimen than harming your noggin. So the next time you try your hands at something new, especially something that requires physical exertion, keep the following unspoken commandment in mind: “Thou shalt not scathe thine neurones.” Abiding by this simple and self-evident edict will enable you to thrive for years to come while continuing to learn and grow as an individual.

REFERENCES

Christiansen, L., Larsen, M. N., Madsen, M. J., Grey, M. J., Nielsen, J. B., & Lundbye-Jensen, J. (2020). Long-term motor skill training with individually adjusted progressive difficulty enhances learning and promotes corticospinal plasticity. Scientific reports, 10(1), 15588.

Gazerani, P. (2025). The neuroplastic brain: current breakthroughs and emerging frontiers. Brain Research, 149643.

Goldberg, H. (2022). Growing brains, nurturing minds—neuroscience as an educational tool to support students’ development as life-long learners. Brain sciences, 12(12), 1622.

Mathias, B., & von Kriegstein, K. (2023). Enriched learning: Behavior, brain, and computation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 27(1), 81-97.

Newbury, C. R., Crowley, R., Rastle, K., & Tamminen, J. (2021). Sleep deprivation and memory: Meta-analytic reviews of studies on sleep deprivation before and after learning. Psychological bulletin, 147(11), 1215.

Yang, Y., Huang, Z., Yang, Y., Fan, M., & Yin, D. (2025). Time-dependent consolidation mechanisms of durable memory in spaced learning. Communications Biology, 8(1), 535.

“Sifu” is Cantonese for “master” or “skilled teacher” and is a respectful title used to designate one’s kung fu teacher.

Impressive stuff Shahin. Didn’t know you were deep into martial arts the way you are. Very cool and nice weaving this into neural substrates for skill learning and mastery!